A laser and detector in one: a microscopic sensor has been developed at TU Wien, which can be used to identify different gases simultaneously.

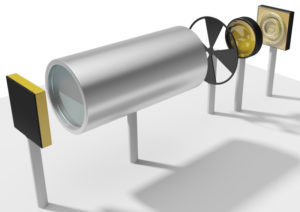

The laser (on the right) sends its light through a gas container, then the beam is reflected by a mirror (left).

As humans, we sniff out different scents and aromas using chemical receptors in our noses. In technological gas detection, however, there are a whole host of other methods available. One such method is to use infrared lasers, passing a laser beam through the gas to an adjacent separate detector, which measures the degree of light attenuation it causes. TU Wien’s tiny new sensor now brings together both sides within a single component, making it possible to use the same microscopic structure for both the emission and detection of infrared radiation.

Circular quantum cascade lasers

“The lasers that we produce are a far cry from ordinary laser pointers ,” explains Rolf Szedlak from the Institute of Solid State Electronics at TU Wien. “We make what are known as quantum cascade lasers. They are made up of a sophisticated layered system of different materials and emit light in the infrared range.”

When an electrical voltage is applied to this layered system, electrons pass through the laser. With the right selection of materials and layer thicknesses, the electrons always lose some of their energy when passing from one layer into the next. This energy is released in the form of light, creating an infrared laser beam.

“Our quantum cascade lasers are circular, with a diameter of less than half a millimetre,” reports Prof. Gottfried Strasser, head of the Center for Micro- and Nanostructures at TU Wien. “Their geometric properties help to ensure that the laser only emits light at a very specific wavelength.”

“This is perfect for chemical analysis of gases, as many gases absorb only very specific amounts of infrared light,” explains Prof. Bernhard Lendl from the Institute of Chemical Technologies and Analytics at TU Wien. Gases can thus be reliably detected using their own individual infrared ‘fingerprint’. Doing so requires a laser with the correct wavelength and a detector that measures the amount of infrared radiation swallowed up by the gas.

A laser that also detects

“Our microscopic structure has the major advantage of being a laser and detector in one,” professes Rolf Szedlak. Two concentric quantum cascade rings are fitted for this purpose, which can both (depending on the operating mode) emit and detect light, even doing so at two slightly different wavelengths. One ring emits the laser light which passes through the gas before being reflected back by a mirror. The second ring then receives the reflected light and measures its strength. The two rings then immediately switch their roles, allowing the next measurement to be carried out.

In testing this new form of sensor, the TU Wien research team faced a truly daunting challenge: they had to differentiate isobutene and isobutane – two molecules which, in addition to confusingly similar names, also possess very similar chemical properties. The microscopic sensors passed this test with flying colours, reliably identifying both of the gases.

“Combining laser and detector brings many advantages,” says Gottfried Strasser. “It allows for the production of extremely compact sensors, and conceivably, even an entire array – i.e. a cluster of microsensors – housed on a single chip and able to operate on several different wavelengths simultaneously.” The application possibilities are virtually endless, ranging from environmental technology to medicine.

Original publication: Rolf Szedlak et al., ACS Photonics, 2016, 3 (10). DOI: 10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00603

Further information – Rolf Szedlak, MSc Institute of Solid State Electronics TU Wien

Source: TU Wien